With the release of the 2020 feedback report detailing the 2.2% maximum possible payment adjustment and the release of the 2022 Final Rule, CMS has demonstrated that MIPS will be both financially rewarding and challenging, in terms of reporting requirements, in 2021 and beyond.

This is the third in a series of blog posts on the 2020 payment adjustment and the 2022 Final Rule, that reviews current and upcoming challenges for MIPS reporting and how the effects of the changes make scoring much more difficult. Our focus in this discussion is on large practices. It will also demonstrate how CMS has progressively closed loopholes for large practices to have their performance represented by only a few clinicians. CMS is slowly adapting the MIPS program to make MIPS scoring more broadly representative of clinician performance throughout a practice.

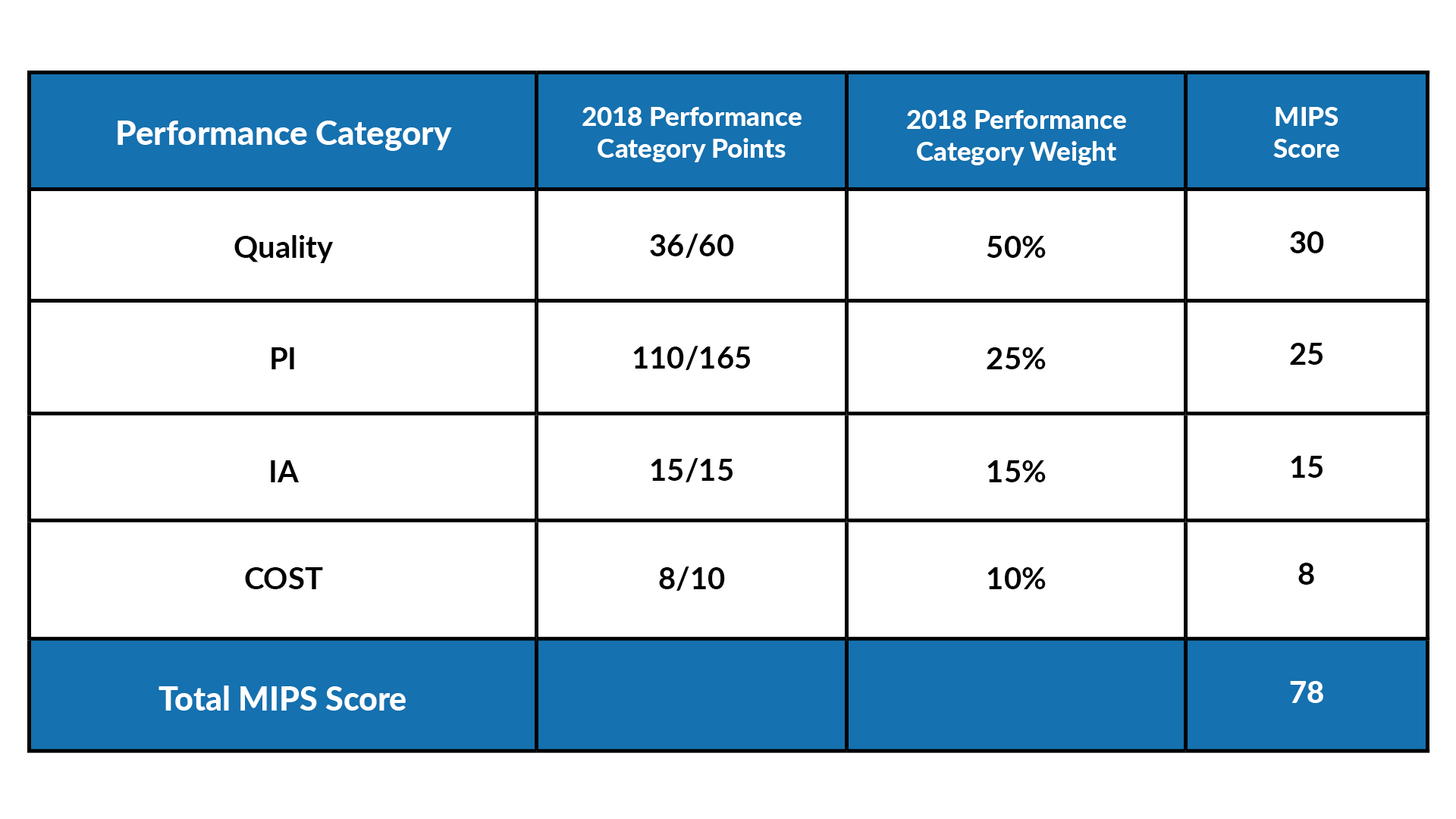

In the charts below, we show a sample practice’s scores in 2018 and in 2021 and consider how the changes in performance categories requirements affect the practice’s score for other performance categories. Our example presumes our practice doesn’t change their reporting strategy year-over-year. This is intentional as we want to highlight the cumulative effect of changes, year-over-year. The chart below depicts how a large, multi-specialty practice might score in MIPS in 2018. The practice earned an overall score of 78 points (exceptional performance), which was also very close to the mean score for 2018 (77).

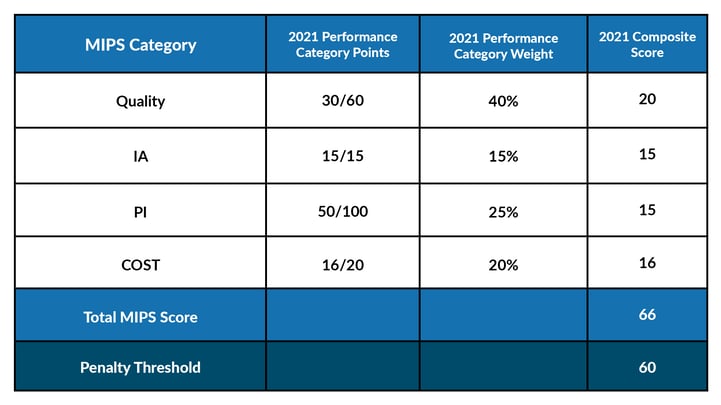

Because of the change to performance category weights, benchmarks, and bonus points (the latter not displayed here), if this practice selects the same Quality measures and Improvement Activities, and earns approximately the same performance points in each category, the practice has to do a lot more work in performance year 2021 than in 2018 to achieve an equivalent score, or more likely a lower score for these performance categories. The more profound changes to Promoting Interoperablity (PI) scoring also mean a much lower PI score for approximately the same performance points. (For simplicity, we have kept the Cost scores the same for both years.) As you can see below, the “older strategy” from 2018 achieves only a score of 64 and narrowly avoids the payment adjustment in 2021.

Because of the change to performance category weights, benchmarks, and bonus points (the latter not displayed here), if this practice selects the same Quality measures and Improvement Activities, and earns approximately the same performance points in each category, the practice has to do a lot more work in performance year 2021 than in 2018 to achieve an equivalent score, or more likely a lower score for these performance categories. The more profound changes to Promoting Interoperablity (PI) scoring also mean a much lower PI score for approximately the same performance points. (For simplicity, we have kept the Cost scores the same for both years.) As you can see below, the “older strategy” from 2018 achieves only a score of 64 and narrowly avoids the payment adjustment in 2021.

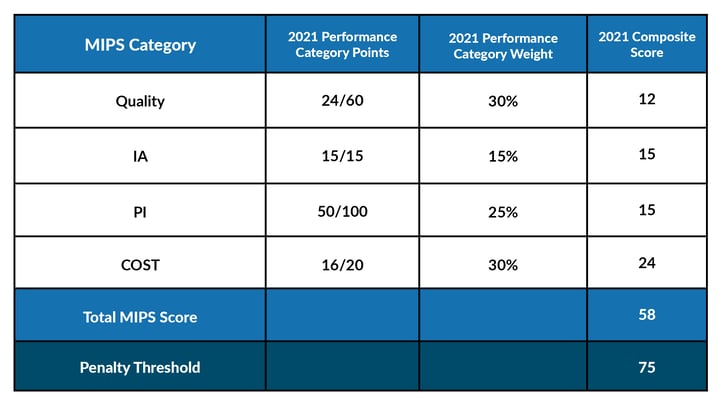

Now, let’s look ahead to 2022. Even with the modest improvement to the PI score depicted below, the PI score improvement cannot compete with the overall changes in difficult for reporting the Quality performance category, as explained in our last blog. (The chart below presumes a loss of only six bonus points—some practices will experience twice as many lost points!). Our 2022 practice scenario yields an even lower score of 58%, which will not meet the minimum threshold requirement of 75 points in 2022.

As shown in these graphs, the score continues to decrease each year, even with the overall performance points earned in each category being roughly equal.

CMS’s rationale for changing performance category scoring year-over-year:

- Goal of pushing large, multi-specialty practices to participate fully in MIPS

A focus on making it more difficult to score well in MIPS overall

Quality

- In 2018, large and small practices would have received three points for measures that didn't meet the data completeness threshold.

- By 2021, large practices receive zero points, while small practices continue to receive three points.

- In 2022, measures with benchmarks will not have the three-point floor “cushion” all practices are accustomed to bumping up their score.

- In 2022, there will be no bonus points awarded to any Quality measures for small or large practices.

The cumulative result of CMS’s changes means it is increasingly important that practices do well with performance itself, rather than taking advantage of bonus points. The plus side of this is that it focuses on performance rather than the complex web of scoring nuances made more complex by bonus point scoring rules. On the other hand, CMS’s changes also disincentivizes the reporting of any “extra” measures, and does not continue to reward the transition or utilization of CERHT.

Promoting Interoperability

Of all performance categories other than Cost, Promoting Interoperability has seen the most dramatic changes to the difficulty in scoring well in the category. For the most part, the scoring rules are agnostic to the size of the participating organization and simply make achieving points more difficult for all organizations. In 2018 it was possible for a practice to earn a total of 165 points in PI. Fifty percent points were awarded for completing the base measures, an additional 90% could be awarded for performance measures (we’re already above 100), and 25% in bonus points. How generous compared to today’s standards! Starting in 2019, CMS offered less flexibility with only one set of measures for the 2015 CEHRT. By 2021, there are only 110 possible points, with only one measure that can earn bonus points. These changes really emphasize the adoption of the CEHRT technologies outlined in the PI measures themselves and encourage the transition to 2015 CEHRT.

Furthermore, 2021 is the first year that clinicians and groups cannot avoid the MIPS payment adjustment through Quality and Improvement Activities alone, even with perfect performance in those categories (approximately 55 points). Although this may not seem dramatic for practices participating in Promoting Interoperability in early years of the program, there is almost no leniency for new adopters of PI to “learn the ropes”, and most cannot opt-out anymore. The only way to accurately estimate that your organization has met the 60-point requirement is through reporting PI or claiming a PI exception.

Improvement Activities

Although meeting reporting requirements for Improvement Activities is not usually an onerous task, CMS raised the bar for groups by increasing the participation threshold requirement from one clinician in the group to 50% of the clinicians in the group in 2020. In 2019, they also eliminated the bonuses for CERHT adoption and utilization offered in 2017 and 2018. Although it is not a change, it should be mentioned that large practices are typically required to report twice the points compared to small practices in order to earn the full 15 points for Improvement Activities. Take, for example, one of the most popular Improvement Activities: IA_AHE_1: Engagement of New Medicaid Patients and Follow-up, a high weighted activity worth 20 points. Small practices could satisfy their reporting requirements and earn the full 15 points. This same activity would only count for half of the requirement for large practices, earning 7.5 points, and requiring 20 additional points to earn the full 15 IA performance category points. Again, the emphasis is on performance over bonus points, and full participation for large practices.

Cost

While large, multispecialty groups are often scored on Cost, the performance category is still haunted by a lack of measures appropriate to all specialties and clinical situations. (Which CMS has admitted to as much during their discussion of subgroup reporting MVPs in the 2022 Proposed Rule. There are currently not enough Cost measures to support MVPs across all specialties. We expect to see this emphasized in future call for measures.) For large and small groups alike that are scored on Cost, they do not usually have reliable ways of estimating their Costs or even knowing all patients that are attributed to them for a performance year. Towards the beginning of the program, this was less impactful to an organization’s final MIPS score. However, beginning in 2022, unless one is partnered with an organization to help them estimate their Cost score, such as our MIPS Cost Analytics, organizations really have no way of being sure they will have exceeded a negative payment adjustment for MIPS.

Special Statuses

Large groups with 15 or fewer clinicians are less likely to qualify for special statuses which will impact their reporting requirements for Improvement Activities and Promoting Interoperability. They won’t automatically qualify for a PI exception due to small practices status (15 or fewer clinicians), and the remaining statuses require that at least 75-100% of the clinicians in the group meet the specific criteria of the status.

Conclusion

The cumulative effect of the evolution of performance category requirements is to nudge the MIPS program toward scoring rules that are tougher on larger organizations, requires active participation from more participants for group reporting, and scores driven by performance points rather than effectively utilizing bonus points. Performing well in the program is more difficult, largely due to the increasing emphasis on a largely unknown and unpredictable Cost score, and the elimination of bonus points for all other performance categories. All of these changes pave the way, however slowly, for mandatory multispecialty subgroup participation in MIPS Value Pathways, expected in 2026. More on that in our next blog.

To ensure that your organization is ready to meet the challenges presented by the evolving MIPS program and the uncertainty of your potential Cost score, check out our MIPSpro packages and contact our team about MIPS Cost Analytics.